Civ VII hit early release today, full release on Tuesday. I gathered my thoughts (purely through paratext!) on the narrative meaning of separated leaders and civilizations, and I look forward to seeing it for myself this weekend.

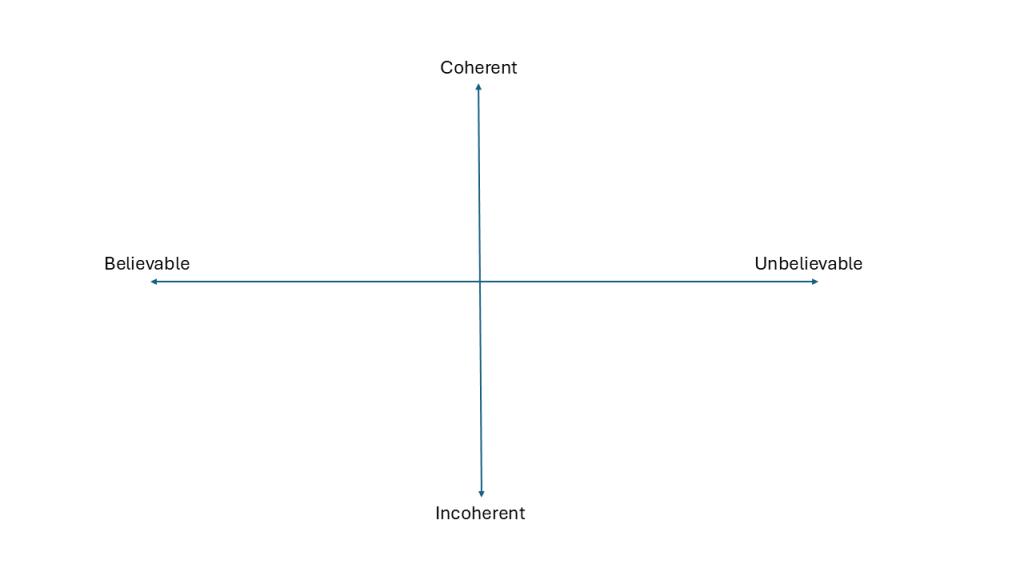

I want to discuss the tension between what I’ve seen in reviews called “real” history and some kind of “weird” other thing. I’m going to call this “believable” and “unbelievable” history, as in, this is a counterfactual I could see happening, or, this is too far past the line of possible for me to accept.

This is not a measure of accuracy, let’s be clear. The goal of Civ is to play through interesting possible histories, to play with interesting historical peoples, and to play with the combinations of those histories and peoples to create interesting narratives of civilizations. I’m interested here in how these peoples, having been separated into leaders and civilizations, generate believable and coherent experiences for players (or not).

These narratives of histories operate along two axes: the believability axis I’ve already described and a coherence axis. Believability is tied to history and the expectations history leaves us with, while coherence is tied to our narrative understanding of what is happening and whether something makes sense as logical.

With that framework established, let’s jump in.

For those unaware, a brief introduction to Civ leaders and civs. In every game of the Civilization franchise, every civ has a leader. Shaka for the Zulus, Napoleon for the French, etc. In past iterations of the game, leaders and civs are inseparable. Leaders represent their civ on the world stage, and the leader’s perks translate into bonuses for the cities and units that belong to their civilization. For example, in Civ 5, Napoleon is leader of the French and grants them the unique Musketeer unit that only the French can build among other perks specific to the French. In Civ 6, the leader-civ relationship gained some complexity. Rulers like Eleanor of Aquitaine had both a French version and an English version reflecting her historical life, or Catherine de Medici having two different versions of herself, both of which lead the French. In each example, these leaders can only lead their respective civilizations, though each combination results in different perks and playstyles.

In Civ VII, this leader-civ relationship is decoupled. Leaders and civilizations are now separate, meaning you can be Napoleon, but now you may be leading the Persians. Napoleon himself seems to no longer be French. He is simply a leader, separated from culture but still representing some aspects of his historical accomplishments. The Persians have their own perks regardless of their leader, ensuring their identity remains stable.

Above, I set up our framework of believable/unbelievable and coherent/incoherent. These are not synonyms. Rather, as we will see, various aspects of the leader-civ relationship align differently within this frame.

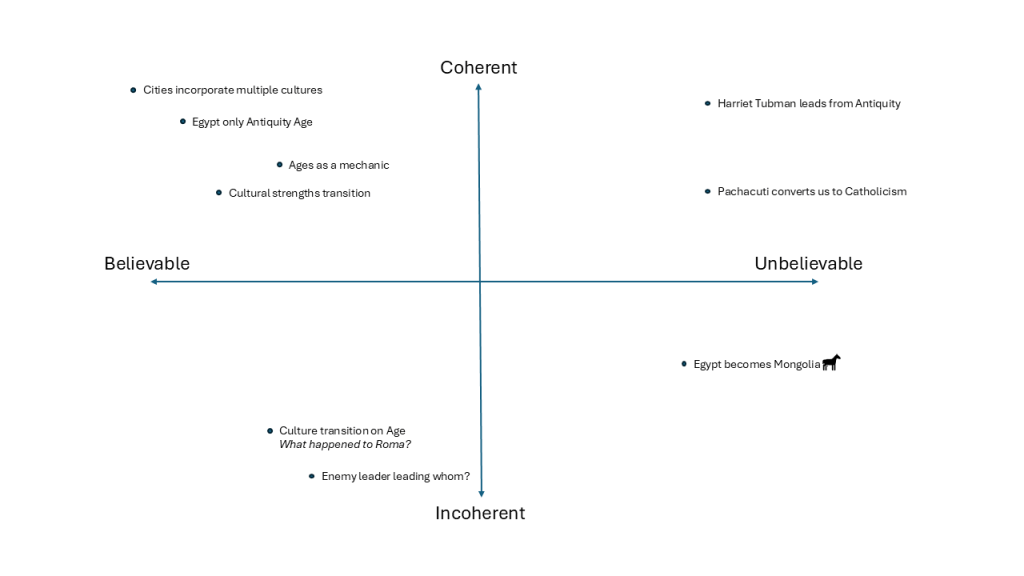

The separation of leaders and civs makes sense within the context of Ages, a now-common 4X mechanic that fully dramatizes and formalizes progress through time. At predictable points in the game, it transitions first from the Age of Antiquity to the Exploration Age, and then later to the Modern Age. At an Act transition, a player is forced to change their civilization. The system solves some noted gameplay problems: it allows for shorter sessions, additional progression feedback, reduced snowballing, etc. In the interest of believable history, it allows civilizations to be depicted at their height, creating more incentives for players to experience them, and allowing additional civilizations to take the stage.

When an Act transitions, as noted, players must select a new civilization to rule. Narratively, this is assumed to be a formalized transition from one culture to another that has happened in many parts of the world many times over. Here at home, we can think of the Native Americans giving way (being replaced by) colonizing Europeans, eventually blending into something new – American culture. This kind of cultural evolution is both believable and coherent. In Civ 7, some cultural trajectories follow historical paths like this, creating an experience that is narratively coherent while also providing new gameplay opportunities. It’s a clean and clever system in these instances.

Some trajectories are not quite as coherent as the one I’ve just described. For example, one may transition from the Egyptians to the Mongols, purely by means of controlling horse resources. This particular possibility is discussed by the developers as a gameplay option especially interesting for players who are less historically-minded. It is interesting design in terms of gameplay evolution, but does it make sense from a narrative perspective? One moment you are Hatshepsut ruling the Egyptians, and the next you’re ruling the Mongols. Do you look like them? Do you sound like them? Does Hatshepsut know anything about nomadic, horse warfare? Who is this Hatshepsut anyway?

Reviewers have already noticed that this can lead to some incoherent and unbelievable experiences:

This whole process is inevitably a little weird … you simply get to mix and match your people, even if it produces extremely weird combos like Machiavelli, leader of ancient Persia. … It also had me thinking about how weird this whole operation is in terms of playing with the figures of history; during one of my sessions I was able to complete an in-game action of securing multiple wine resources, which then allowed me to turn my Hawaiian civilization into the French.” —Cameron Kunzelman, Polygon (emphasis added)

Firaxis prefers to speak about this as allowing a mixture of playstyles, since one’s leader can have strengths that do not match those of a civilization. While true, this gameplay interest creates some dissonance against the narrative interests of play.

Machiavelli, Persia, Hawaii, France – these peoples do not exist independently in our minds. We expect them to behave in certain ways. Certainly, there are many kinds of outcomes they could have followed and may be believable, but there does seem to be some point where they no longer are believable and instead are just “weird,” or as I interpret this, incoherent.

In the Paste review, the author tells a great story about herself as Isabella I leading the Romans until the Act transitions.

“While the Crisis ravaged the Age of Antiquity, the monumental empress gave herself over to the thrill of military expansionism.

And then the Age of Antiquity ended.

Perhaps we’ll never really know what happened to Isabella’s Rome. Did it simply absorb too much of Persia? Were there famines and plagues? Populations migrated and dispersed and intermingled. Culture changed.” —Dia Lacina, Paste

Isabella (or her player rather) describes Rome as a city absorbing cultures, but one that also disappears into irrelevance. She moves her capital to Milan (renamed to Madrid) and leaves us to wonder what happened to Roma?

Cities on Age transition retain their wonders and culturally significant buildings (like the Roman forum) even as a new culture begins building its own unique architecture. This results in a beautiful and believable tapestry of cultural layers on your map. One oddity stands out. When your civilization changes, your palace’s visual identity immediately swaps from your old culture to your new culture. While your forum and coliseum may remain, your palace gets an instant facelift. This incoherence reflects the unclear narrative of an Age transition. Isabella’s response to the crisis that ended the Age was swift and successful. So why does Rome fall? Perhaps her decision to move her capital to Madrid reflects an effort on her own part as the player to recover some coherence. Using incoherence as a lever to encourage players to create an emergent narrative to make sense of play is an unusual approach.

While Isabella’s player was motivated to retain coherence in herself and the empire she rules, how do players feel about their rivals? One of Firaxis’ main motivations for keeping rulers static was their attempt to retain the coherent narrative of one’s self and allies against the rival Other(s). But if my rival is a name I recognize but do not know on the map, this is incoherent.

“Given that Civ 7’s otherwise slick-looking animated leaders don’t change at all visually through the Ages, you end up with some confusing situations like having Ben Franklin declare war on you and then having to look up what civ he’s actually controlling right now. Persia? Ooookay.” — Leana Hafer, IGN (emphasis added)

I am reminded of my question above – who is Hatshepsut anyway? While cities reflect change over time, leaders remain static and immortal. Is it Hatshepsut at all or just an avatar of the player with a familiar name?

In former iterations of the series, a leader was both the avatar of the player and an individual representation of their civilization. I was both Eleanor of Aquitaine and French. Perhaps I am an anomaly, but I tend to play the French often, regardless of who they rule. The leader is a convenient reference point for the fuller identity of the culture they embody. Or at least they were. I cannot think of Napoleon without thinking of the French, or of Benjamin Franklin without thinking of America. Players have noted that having America start in antiquity was a bit awkward – is it more or less awkward to have only Benjamin Franklin start there?

Civ 7 has a new narrative system that employs storylets to surface interesting narrative elements of a playthrough. It’s the system I am most excited about trying out this weekend. This narrative system could be used to reinforce areas where coherence slips and provide continuity in areas where transitions leave the narrative unclear. We could find areas where Benjamin Franklin as a leader resonates with his civilization and surface those to the player. We could provide narratives to drive and explain the changes to Roma at an act transition. It is a balance between driving behavior and responding to it, but it’s one with great potential.

Believability, however, is more difficult to repair through narrative.

“There’s something very uncomfortable about Pachacuti converting people to Catholicism.” —Sin Vega, Eurogamer

Pachacuti was a famous ruler of the Incas in the period shortly before the Spanish conquest. He never knew Catholicism, but that isn’t what makes this uncomfortable. Less than a century after his death, the Spaniards had conquered the Incas, and with them they had brought Catholicism. It became a weapon deployed to destroy the culture of the Incas, all in the name of the salvation of souls.

Presumably in this player’s game, Pachacuti founded Catholicism as his (possibly not Incan) civilization’s religion and went on to convert followers as one does. This is a coherent action for him to take in the context of the game. We could maybe even imagine a world where the Spaniards were only missionaries instead of colonizers and by some miracle, Christianity became a part of Incan culture rather than supplanting it. But that is a counterfactual that is so counter to fact as to be unbelievable, at least to this player. It didn’t even matter what the civilization of the current Age was – Pachacuti himself was the Incas to this player, and it made this experience a negative one.

It reminds me of an experience I had in Humankind. After a long time away, I began a game playing the Nubians. At some point, I saw myself in the diplomacy screen as a white woman and was caught off guard. Why am I white, I asked, I’m Nubian. But no, I was just an avatar separated from my people.

Even counterfactuals are grounded in the reference points of history, and as such they have constraints on their possibility. Players decide that line and determine at which point something can be believed to be so. The decoupling of leaders and civilizations creates instances where dissonance can arise between coherence and believability, and it will be interesting to see (and experiment with) how narrative can help soften these effects.

Leave a comment